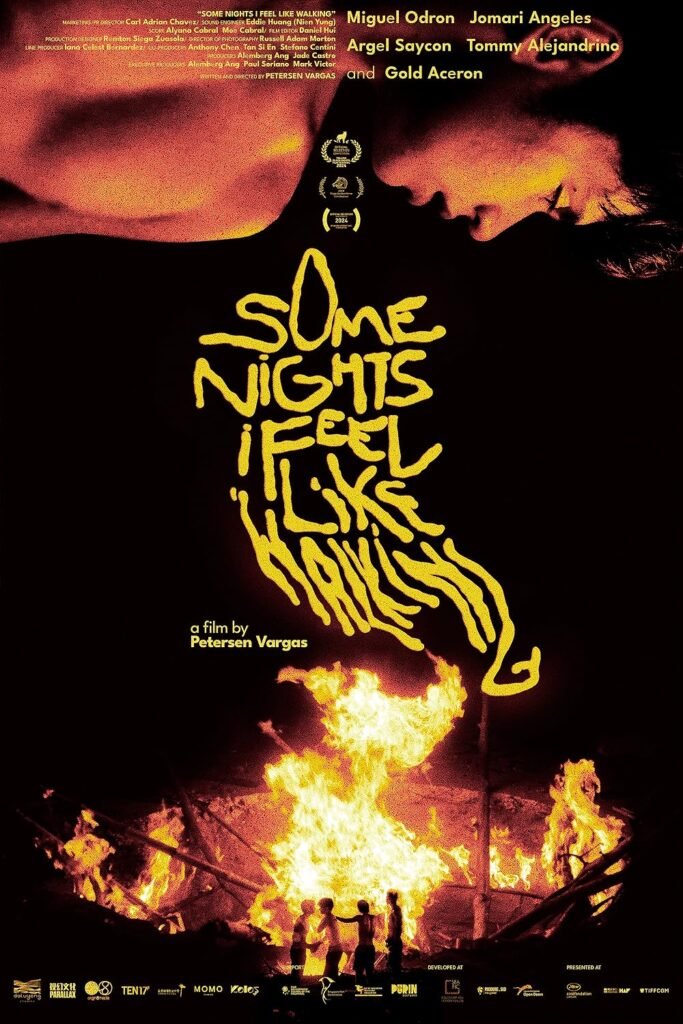

EDITOR’S NOTE: Some Nights I Feel Like Walking is an ESSENTIAL VIEWING

IF SOMEONE CATALOGED the geographies of one’s queerness — the nooks we’ve determined safe to inhabit, the fringes of town we call ours, that small patch of land we embed with fond meaning and memory — one would have in their hands a scrawny-thin atlas. Though meager, each chapter would map these journeys both breathtaking and bruising. At least that’s what it felt watching Petersen Vargas’ new film, Some Nights I Feel Like Walking, a loving ode to found spaces for people who have all been but lost.

The film, which reads like an expansion of Vargas’ 2020 short film, How to Die Young in Manila, follows a young boy named Zion (Miguel Odron) who dips into the seedy underbelly of a city ruled by corruptive violence and carnal desires. Or that’s how it starts anyway. The first half of Some Nights tees up this expectation typical of a certain type of film, but it unravels into something different. Touted as a “queer road movie,” Some Nights turns into this close-up portrait of youths on fire — neglected, expelled, and misunderstood. And so, they walk.

Yet, that is not what the film is about, at least not completely. Given its subject, Some Nights does skirt about the politics of everything but it never does so that it feels too didactic. One character notes that we don’t own our bodies, a throwaway comment that, the longer it sits in one’s head, the harsher a truth it becomes.

The film’s young hustlers — Rush (Tommy Alejandrino), a wise firecracker doubtless in tribute to his name (iykyk), Miguelito (Gold Azeron), the group’s beating heart, Bayani (Argel Saycon), a cherub-faced adonis, and Uno (Jomari Angeles), their charismatic leader — seem perfectly attuned to the cards they have been dealt. They yearn for the same things in life as you and I. And although the film is very much Uno’s story intertwined with Zion’s, the rest of its characters feel fully realized, thanks largely to the actors’ performances.

Vargas’ direction has finally outgrown all the flashy Dolan-isms that deter him from realizing his vision as a filmmaker. Here, he’s swapped them with gorgeously lensed scenes of Manila, care of Singaporean DOP Russell Morton, whose work in In My Mother’s Skin still haunts me. Vargas’ depiction of Manila is luminous, bedecked with blinding neon lights but helpless about its indelible grime. The end-picture still registers like a Petersen Vargas film, but I’d be remiss not to mention how big of an upgrade Some Nights is, visually.

Along with Daniel Hui’s editing, the visuals propel Vargas’ screenplay, which, some might complain, meander a bit around the middle. The bus dream sequence — Petersen, have you been watching Kiyoshi Kurosawa? — can feel oddly placed, and things resolve at the end a bit too briskly. But there’s something about that scene that feels integral to the film: how many regretful decisions have we had to make as queer folk? How does one reconcile with our past and move on? Vargas generously draws from his own experiences and finds for us a path.

That brings us to the film’s finale, a tense twenty-or-so-minute oner that leads us in front of a large, flickering bonfire. The boys strip down to their bare chests, exposing the identical scorched flesh on their sides. They weep, mourning the same brunt they’ve had to bear and grieving what they each have lost. In front of disapproving eyes, they embrace. The film sits with this moment. Then, cautiously the camera pushes in, as if it means to include us in this warmth engulfing its characters. That moment feels nice knowing that, like them, I shall never die alone.